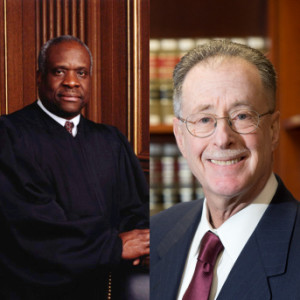

Utah v. Strieff, 579 U.S. ___ (2016) (Thomas, J.).

Response by Stephen Saltzburg

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (Oct. Term 2015)

Slip Opinion | New York Times | SCOTUSblog

Chipping Away at the Exclusionary Rule

The Supreme Court’s decision in Utah v. Strieff,1 on June 20, 2016, looks at first blush like a minor limit on the scope of the Fourth Amendment exclusionary rule. But a closer look reveals that its practical effect might be to greatly enhance law enforcement incentives to make “stops” without the necessary reasonable suspicion and might affect a large number of people.

The facts of the case are relatively simple: South Salt Lake City police received an anonymous tip of “narcotics activity” at a particular residence. Narcotics detective Douglas Fackrell investigated the tip and, over the course of a week of intermittent surveillance of the home, he saw people arriving and leaving after a few minutes. Fackrell saw Edward Strieff exit the house and walk toward a nearby convenience store. Fackrell detained Strieff in the store’s parking lot, identified himself, asked Strieff what he was doing at the residence, and requested Strieff’s identification which he relayed to a police dispatcher. The dispatcher responded that there was an outstanding arrest warrant for Strieff for a traffic violation. Fackrell arrested Strieff and discovered a baggie of methamphetamine and drug paraphernalia in a search incident to the arrest. Strieff entered a conditional guilty plea to drug charges.

The state court of appeals affirmed the conviction, but the state supreme court reversed on the ground that the arrest and search were fruits of an unconstitutional stop (i.e., one lacking reasonable suspicion). The Supreme Court of the United States reversed and held that the exclusionary rule did not require suppression of the drug evidence.

Justice Thomas, who wrote for the Court, began his legal analysis with a description of the exclusionary rule and three principal exceptions to the rule: independent source, inevitable discovery, and attenuation. The third exception was the focus of the rest of his opinion. The Court’s bottom line was set forth in the final sentence of the opinion’s opening paragraph: “We hold that the evidence the officer seized as part of the search incident to arrest is admissible because the officer’s discovery of the arrest warrant attenuated the connection between the unlawful stop and the evidence seized incident to arrest.”2

Justice Thomas relied upon Brown v. Illinois3 as establishing a three factor approach to attenuation: (1) temporal proximity between the initially unlawful stop and the search; (2) the presence of intervening circumstances: and (3) the purpose and flagrancy of the official conduct. He reasoned that the first factor “favors suppressing the evidence”; the second factor “strongly favors the State”; and the third factor “also strongly favors the State.”4

In analyzing the second factor, Justice Thomas relied upon Segura v. United States.5 In that case, agents had probable cause to believe that apartment occupants were dealing cocaine, sought a warrant, and entered the apartment while a warrant was sought. They arrested the occupants and discovered drug evidence in a limited search they conducted for security purposes. The next evening a magistrate issued a search warrant without relying on anything found in the apartment. The Court held that the evidence found in the search pursuant to the warrant was admissible.

Justice Thomas acknowledged that Segura relied on the independent source doctrine, not attenuation, but reasoned that the Strieff arrest warrant was valid and was entirely unconnected with the stop and the search incident to the arrest was conducted only after a valid arrest was made.

As for the third factor, Justice Thomas concluded that Fackrell “was at most negligent” and “made two good-faith mistakes” (not observing how long Strieff was in the house and not asking whether he could speak to Strieff rather than commanding him to speak)6. Justice Thomas further concluded that “these errors in judgment hardly rise to a purposeful or flagrant violation of Strieff’s Fourth Amendment rights” and “there is no indication that this unlawful stop was part of any systemic or recurrent police misconduct.”7

The Court’s majority included the Chief Justice and Justices Kennedy, Breyer and Alito. Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan filed dissents, each of which was joined by Justice Ginsburg (except for Part IV of Justice Sotomayor’s dissent).

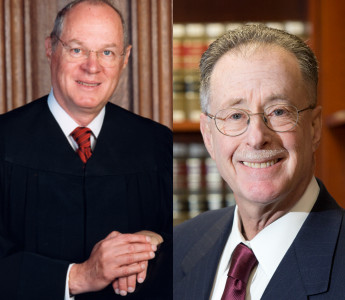

Justice Sotomayor observed that it is tempting in this kind of case “to forgive the officer,” because “his instincts, although unconstitutional, were correct.”8 But she concluded that this was not a case of attenuation, given “the officer in this case discovered Strieff’s drugs by exploiting his own illegal conduct.”9 She expressed concern about the practical impact of the decision, noting that Utah lists over 180,000 misdemeanor warrants in its database and had a huge backlog of outstanding warrants at the time of the stop and arrest of Strieff. She also cited data on outstanding warrants in other jurisdictions that indicate that the States and the Federal Government maintain databases with more than 7.8 million outstanding warrants and relied on the Utah Supreme Court’s earlier decision revealing that Salt Lake City police officers routinely run warrant checks on pedestrians they detain without probable cause.

Justice Sotomayor disagreed entirely with the argument that Segura supported the majority’s approach, arguing that the agents in that case conducted a search that had nothing to do with the warrant they obtained. Conversely, Fackrell’s “illegal conduct in stopping Strieff was essential to his discovery of an arrest warrant.”10

Part IV of Justice Sotomayor’s opinion begins with this paragraph:

Writing only for myself, and drawing on my professional experiences, I would add that unlawful “stops” have severe consequences much greater than the inconvenience suggested by the name. This Court has given officers an array of instruments to probe and examine you. When we condone officers’ use of these devices without adequate cause, we give them reason to target pedestrians in an arbitrary manner. We also risk treating members of our communities as second-class citizens.11

In a part of her opinion that will surely be widely quoted, she wrote:

The white defendant in this case shows that anyone’s dignity can be violated in this manner. See M. Gottschalk, Caught 119-138 (2015). But it is no secret that people of color are disproportionate victims of this type of scrutiny. See M. Alexander, The New Jim Crow 95-136 (2010). For generations, black and brown parents have given their children “the talk”—instructing them never to run down the street; always keep your hands where they can be seen; do not even think of talking back to a stranger—all out of fear of how an officer with a gun will react to them. See, e.g., W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903); J. Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1963); T. Coates, Between the World and Me (2015).12

In her dissent Justice Kagan applied the three factors drawn from Brown, agreed with the majority’s temporal analysis, found that Fackrell’s Fourth Amendment violation was “far from a Barney Fife-type mishap”,13 and concluded that there was nothing unforeseeable about the warrant discovery so that it was hardly the kind of event that should be deemed to have broken the causal chain between Fourth Amendment violation and evidence discovery. She too relied on the routine practices of Salt Lake City police and national data on the large number of outstanding warrants.

- Utah v. Strieff, No. 14-1373, slip op. (U.S. June 20, 2016).

- Id. at 1 (majority opinion).

- Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590 (1975)

- Strieff, slip op. at 6, 7–8.

- Segura v. United States, 468 U.S. 796 (1984)

- Strieff, slip op. at 8.

- Id.

- Id. at 2 (Sotomayor, J., dissenting).

- Id. at 4.

- Id. at 6

- Id. at 9-10.

- Id. at 11-12.

- Id. at 3 (Kagan, J., dissenting).

Recommended Citation:

Stephen Saltzburg, Response, Utah v. Strieff: Chipping Away at the Exclusionary Rule, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (June 23, 2016), http://www.gwlr.org/utah-v-strieff-chipping-away-at-the-exclusionary-rule/.