Evenwel v. Abbott, 578 U.S. ___ (2016) (Ginsburg, J.).

Response by Dean Alan Morrison

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (Oct. Term 2015)

Slip Opinion | New York Times | SCOTUSblog

Redistricting—When Whom You Count Really Counts

In one respect, the nature of the challenge made the Court’s decision in Evenwel relatively easy because the plaintiffs’ claim was that Texas had no choice but to use eligible voters as the base for redistricting. Therefore, all the Court had to decide was whether the Constitution compelled that result in the face of the fact that every state has used total population as the basis for allocating seats in both of its legislative bodies since 1964 when the Court in Reynolds v. Sims3 made equality the touchstone for drawing all legislative districts. Plaintiffs also complicated their task because, in asking the Court to hear this case, they argued that counting only those eligible voters who were actually registered could also be a constitutionally valid way to draw voting districts. In making this argument, they never explained how the Constitution could allow both of their preferred alternatives but preclude states from using total population.

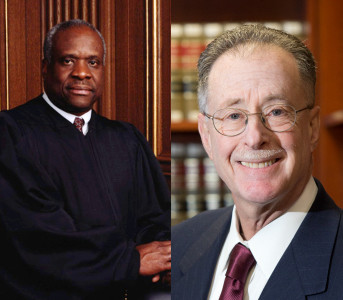

The majority opinion written for six Justices by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who also authored last term’s Arizona Legislature majority, mainly relied on two separate lines of argument. First, she observed that Article 1, section 2, clause 3 of the Constitution provides for election to the U.S. House of Representatives with apportionment “according to their respective Numbers,” and that the constitutional history makes it clear that the apportionment was tied to the census, which includes everyone, not just eligible voters. Second, she reviewed the history of the development of the districting provisions that were changed by the Fourteenth Amendment to eliminate the rule that slaves counted for only three-fifths of a person in making apportionments. Her opinion cites many statements from the congressional debate embracing the notion that the new apportionment would include everyone, voters or not, which at that time excluded women and children as well as non-citizens. Given that understanding of how apportionment works at the federal level, she concluded that it was surely permissible for states to follow that same approach when they allocated seats in their legislatures. For those reasons, the majority concluded, as Texas had urged, that the State did not violate the Constitution by declining to use voter-eligible population as the basis for its re-apportionment.

The United States opposed the plaintiffs as amicus curiae, but it took a different position: Not only did Texas not have to use voter population as the plaintiffs urged, but the Constitution compels all states to use total population. In this case, the result was the same, but in the next one, it might not be. Indeed, Texas formerly used voter population to apportion seats in its Senate and changed to the current system only after it received a 1981 opinion from the Texas Attorney General that using voter population was unconstitutional. But Justice Ginsburg would not now decide the next case: “We need not and do not resolve whether, as Texas now argues, States may draw districts to equalize voter-eligible population rather than total population.”4 Now that the idea of voters as the basis for allocation is out of the bottle and possibly lawful, however, it seems quite likely that some states will try it. Because the outcome of a voter-based system would be to reduce representation for communities with large numbers of children and non-citizens, a decision to use voters as the base would not be because the result would be more democratic, but because it seems likely to favor the political party proposing it.

Today’s decision did not rely on the practicality of using the ten year census, which is required by the Constitution and which has a high degree of acceptance and reliability, but other options present very real practical problems. For example, to ascertain eligible voters, plaintiffs had suggested that “jurisdictions should design districts based on citizen-voting-age population (CVAP) data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), an annual statistical sample of the U. S. population.”5 But when one examines that data,6 there are no clean and accepted numbers like those in the census. This can be seen from a link on that page to a memorandum that explains the basis for the data that appears in that sample.7 First, unlike the actual enumeration in the census, the numbers here are estimates which are used for allocating federal and state funds, not for legislative seats. Second, the numbers cover a five year period, whereas the census is a snapshot of the country as of April 1 in the decennial year. Third, these numbers include a major category of citizens over the age of 18 who are not eligible to vote: convicted felons whose rights have not been restored. Fourth, there are many cities, including the District of Columbia and probably New York and San Francisco, where young adults and others live but continue to vote elsewhere, further making this a less desirable apportionment basis, even if one were inclined to prefer voter-based allocation over those relying on total population.

Justice Clarence Thomas filed a concurring opinion in which he would have upheld the decision of Texas to use total population, but for a reason quite different from the majority’s. According to Justice Thomas,

The Constitution does not prescribe any one basis for apportionment within States. It instead leaves States significant leeway in apportioning their own districts to equalize total population, to equalize eligible voters, or to promote any other principle consistent with a republican form of government. The majority should recognize the futility of choosing only one of these options.8

His rationale extends far beyond this case to invalidate all of the state re-apportionment cases beginning with Reynolds. Thus, should there be a case in which a state opts for voters as the base, Justice Thomas will surely support that choice.

Justice Samuel Alito also concurred, but his opinion did not indicate which way he would come out in the next case. He agreed that Texas had the leeway to make this choice, but he rejected the majority’s reliance on the analogy to how districts for the House of Representatives are drawn (in which Justice Thomas concurred), and on the relevance of the debates concerning Congressional re-apportionment leading up to the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment (which Justice Thomas did not join).

There is one additional point that is worth considering regarding the Texas (and Justice Thomas’) approach of leaving it up to the States, so long as the result produced numerically equal districts. Under this approach, States are not simply required to choose one method and stick with it forever. Rather, if they have free choice, there is no reason why they cannot change as often as they wish. Presumably, that would include whenever the legislature (or perhaps voters via a citizen initiative) decided to change the system for partisan political advantage over what preceded it. Indeed, if States may choose, they would not be limited to the alternatives at issue in Evenwel, but could employ other systems, such as registered voters, those who actually voted in a recent statewide election, or anything else that might have some basis in equality and voting. Whether these considerations have a constitutional dimension is not clear, but they surely should be potent ammunition when alternatives to total population are proposed and citizens are asked to support them through their elected representatives (or perhaps a form of direct democracy, which is how the Arizona redistricting commission was created).

- Evenwel v. Abbott, No. 14-940 (U.S. Apr. 4, 2016).

- Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Comm., 135 S. Ct. 2652 (2015).

- Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964).

- Evenwel v. Abbott, No. 14-940, slip op. at 18.

- Id. at 7.

- Redistricting Data: Voting Age Population by Citizenship and Race, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/rdo/data/voting_age_population_by_citizenship_and_race_cvap.html (last visited Apr. 4, 2016).

- U.S. Census Bureau, Citizen Voting Age Population (CVAP) Special Tabulation From the 2010-2014 5-Year American Community Survey (ACS) (2015), https://www.census.gov/rdo/pdf/CVAP_10to14_Documentation.pdf.

- Evenwel, slip op. at 1-2 (Thomas, J., concurring).

Recommended Citation

Alan B. Morrison, Response, Evenwel v. Abbott, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (Apr. 05, 2016), http://www.gwlr.org/evenwel-v-abbott-redistricting-when-whom-you-count-really-counts/.