March 6, 2017

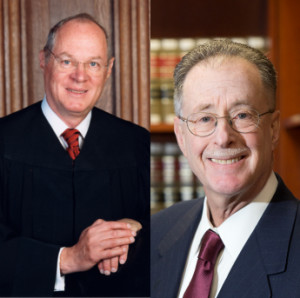

Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado, 580 U.S. ___ (2017) (Kennedy, J.).

Response by Professor Stephen Saltzburg

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (Oct. Term 2016)

Slip Opinion | New York Times | SCOTUSblog

Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado: The Ultimate Safeguard Against Juror Racial Bias?

The Issue

On March 6, 2017, the Supreme Court resolved an important question related to post-conviction juror impeachment, holding that an exception to the no-impeachment rule exists when a defendant is able to show post-trial substantial evidence of a juror’s racial bias or animus.

The Charges and the Trial

In 2007, a man sexually assaulted two teenage sisters in the bathroom of a Colorado horse-racing facility. The girls told their father and identified the man as a racetrack employee, Miguel Angel Peña-Rodriguez. The police located and arrested the defendant, and each girl separately identified him as the man who had assaulted her. The Colorado Court of Appeals reported that the prosecution at trial relied upon the pre-trial identifications and in-court identifications by the victims. However, the prosecution presented no physical evidence while the defendant relied upon a single witness who testified that he was with the defendant at a different location when the assaults occurred.

Post-Trial Developments

After a Colorado jury convicted Peña-Rodriguez of harassment and unlawful sexual contact and rejected his mistaken identification defense, two jurors informed defense counsel and submitted affidavits alleging that another juror (H.C.) had expressed anti-Hispanic bias toward the defendant and his alibi witness. The trial court recognized H.C.’s apparent bias but held that Colorado Rule of Evidence 606(b) barred a court from inquiring into a jury’s deliberations to impeach a verdict except in limited circumstances that were inapplicable to this case. Both the Colorado Court of Appeals and the Colorado Supreme Court agreed and rejected constitutional challenges to the state rule. The U.S. Supreme Court granted review to address “the question whether there is an exception to the no-impeachment rule when, after the jury is discharged, a juror comes forward with compelling evidence that another juror made clear and explicit statements indicating that racial animus was a significant motivating factor in his or her vote to convict.”1

The Holding

There can be no doubt that Colorado courts are entitled to interpret their rules of evidence as they deem appropriate. The U.S. Supreme Court lacks jurisdiction to review a state court’s decision interpreting its own law, but it clearly has jurisdiction to decide whether a state law (including a rule of evidence) is inconsistent with the U.S. Constitution. The defense’s argument in Peña-Rodriguez was that the limitation of post-verdict impeachment was inconsistent with the Sixth Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed with that argument and stated that “the Court now holds that where a juror makes a clear statement that indicates he or she relied on racial stereotypes or animus to convict a criminal defendant, the Sixth Amendment requires that the no-impeachment rule give way in order to permit the trial court to consider the evidence of the juror’s statement and any resulting denial of the jury trial guarantee.”2 Justice Kennedy wrote for the 5-3 majority and was joined by Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan.

Jury Selection and Allegations as to H.C.

The trial judge gave prospective jurors a written questionnaire that asked if there was “anything about you that you feel would make it difficult for you to be a fair juror.”3 The judge then orally asked the same question to the prospective jurors and encouraged them to speak with the court privately if they had any concerns about their impartiality. None of the empaneled jurors expressed reservations about bias nor did any ask to speak privately with the judge.

The jury returned its verdict after a three-day trial, and the judge instructed the jurors that it was up to them whether to talk with anyone about the trial. Defense counsel went into the jury room to talk with jurors. Two of the jurors remained as others left, and they informed defense counsel about H.C.’s statements during deliberations. Defense counsel reported this to the judge and obtained affidavits from the jurors under the judge’s supervision.

Allegations as to H.C.

The juror affidavits alleged that H.C. told the other jurors that he “believed the defendant was guilty because, in [H.C.’s] experience as an ex-law enforcement officer, Mexican men had a bravado that caused them to believe they could do whatever they wanted with women.”4 The affidavits reported that H.C. stated that Mexican men are physically controlling of women because of their sense of entitlement. They further alleged H.C. said, “I think he did it because he’s Mexican and Mexican men take whatever they want.”5 The jurors additionally claimed H.C. relied on his experience to say that “nine times out of ten Mexican men were guilty of being aggressive toward women and young girls.”6 Finally, the affidavits alleged H.C. said that he rejected the alibi witness’s credibility because he was “an illegal.”7

The Common Law and Supreme Court Precedent

Justice Kennedy traced the history of the no-impeachment rule from Vaise v. Delaval,8 an eighteenth-century decision by Lord Mansfield excluding juror testimony that the jury had decided the case through a game of chance. He proceeded to detail the subsequent development of “the Mansfield rule,” which prohibited jurors from impeaching verdicts by testifying either about (a) their subjective mental processes or (b) about objective events that occurred during deliberations. Justice Kennedy noted that some American jurisdictions adopted “the Iowa rule” that rejected the second limitation of the Mansfield rule; federal courts, although not always consistent, largely adhered to both limitations; and both limitations were included in Federal Rules of Evidence 606(b). Justice Kennedy observed that 42 American jurisdictions follow the federal rule, 9 follow the Iowa rule, and 16 jurisdictions—including 11 that follow the federal rule—and 3 federal circuits permit an exception where racial bias might have impacted a verdict.

Justice Kennedy addressed two prior decisions of this Court upon which the Colorado courts had relied: Tanner v. United States9 and Warger v. Shauers.10 In Tanner, the Court rejected a Sixth Amendment argument for an exception to Federal Rules of Evidence 606 (b) when the defendant alleged that jurors were under the influence of alcohol or drugs during the trial. Justice Kennedy pointed out that the Court had identified other safeguards against jurors engaging in substance abuse. In Warger, the Court rejected a losing civil plaintiff’s attempt to use statements in jury deliberations to show that the jury foreperson lied in voir dire when she concealed a pro-defendant bias. The Court had observed that nothing prevented a civil party from raising bias claims pre-verdict or from making them post-verdict without relying on the content of jury deliberations (e.g., testimony from a non-juror that a juror lied during voir dire).

Racial Claims Are Different

Justice Kennedy explained that there is a long history in the United States of racial discrimination threatening the Sixth Amendment guarantee of a fair and impartial jury. He observed that although certain safeguards, like voir dire, observation of jurors during trial, juror reports pre-verdict and non-juror post-verdict evidence, might help to identify racial bias, the stigma associated with racial bias might inhibit jurors from self-identifying or reporting other jurors as biased.

The Court makes clear that there are limits on its decision. “Not every offhand comment indicating racial bias or hostility will justify setting aside the no-impeachment bar to allow further judicial inquiry.”11 The threshold is “a showing that one or more jurors made statements exhibiting overt racial bias that cast serious doubt on the fairness and impartiality of the jury’s deliberations and resulting verdict.”12 It is for a trial judge to determine whether the threshold showing has been satisfied.

Justice Kennedy also observed that lawyers will have to comply with state ethics rules and local court rules when they consider interviewing jurors.

The Dissents

Justice Thomas recognized that although the common law guaranteed a right to an impartial jury, it did not guarantee a defendant the right to impeach a jury verdict with juror testimony about juror misconduct, including partiality.13 He pointed to the various state approaches to limiting juror attacks on verdicts and objected to the Court’s imposition of a uniform national standard.

Justice Alito briefly analogized the no impeachment rule to privileges, like attorney-client, clergy, and spousal, and cautioned against opening jury deliberations to inspection.14 He also argued that it is difficult to demonstrate that the Sixth Amendment is more concerned with racial bias than with other juror misconduct, and he concluded that “[i]f the Sixth Amendment requires the admission of juror testimony about statements or conduct during deliberations that show one type of juror partiality, then statements or conduct showing any type of partiality should be treated the same way.”15

Justice Alito also expressed several other concerns about the implications of the decision. Its reach is unclear as to whether it extends to gender bias or bias covered by the First Amendment. It will be difficult for courts to determine what qualifies as a clear expression of racial bias. The finality of jury verdicts will be undermined and jurors will be subject to increased harassment.

Significance of the Decision

The Peña-Rodriguez majority has made a strong statement about the importance of eliminating racial discrimination to the greatest extent possible from criminal cases. The majority was willing to break from a long-standing reluctance to disturb jury verdicts by examining the deliberations of the jury and left no doubt that it sees racial discrimination as a more serious threat to equal justice and public confidence in verdicts than any other it has confronted. It is highly likely that lower courts will struggle to determine how much evidence of a racial bias or stereotype is sufficient to justify a hearing and how much is needed to set aside a verdict. The majority is obviously willing to impose this burden on lower courts. In rejecting the dissenters’ argument against a uniform national rule, the majority established that there is only one acceptable rule when it comes to racial discrimination in criminal cases: i.e., it will not be tolerated.

- Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado, No. 15–606 (U.S. March 6, 2017).

- Id. at 17.

- Id. at 2.

- Id. at 3–4.

- Id. at 4.

- Id.

- Id.

- 1 T.R. 11, 99 Eng. Rep. 944 (K. B. 1785).

- 483 U.S. 107 (1987).

- 135 S. Ct. 521 (2014).

- Peña-Rodriguez, slip op. at 17.

- Id.

- Peña-Rodriguez, slip op. at 1 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

- Peña-Rodriguez, slip op. at 1 (Alito, J., dissenting).

- Id. at 18 (Alito, J., dissenting).

Recommended Citation Stephen Saltzburg, Response, Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado: The Ultimate Safeguard Against Juror Bias?, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (March 10, 2017), http://www.gwlr.org/pena-rodriguez-v-colorado-the-ultimate-safeguard-against-juror-racial-bias/.