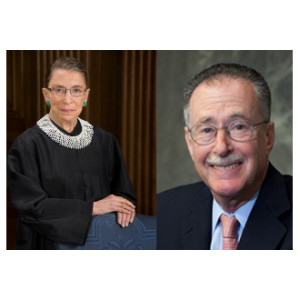

Response by Professor Stephen A. Saltzburg

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (Oct. Term 2014)

Rodriguez v. United States, 575 U.S. ___ (2015)

Docket No. 13-9972; argued January 21, 2015; decided Apr 21, 2015

Slip Opinion | NY Times | SCOTUSblog

Justice Ginsburg’s April 21, 2015 opinion for a six-Justice majority in Rodriguez v. United States1 established nothing new, but rejected reasoning by the Eighth Circuit (which Justice Thomas adopted) that potentially would have opened the door to a variety of heretofore prohibited police practices. The Court’s holding is clearly stated: “We hold that a police stop exceeding the time needed to handle the matter for which the stop was made violates the Constitution’s shield against unreasonable seizures.”2

A K-9 police officer with his dog in the car stopped Rodriguez’s car shortly after midnight when it veered off the highway for one or two seconds onto the shoulder. During the stop, the officer asked for and inspected Rodriguez’s license, registration and insurance cards and asked a passenger for identification, all of which he used to check for outstanding warrants. The officer returned the identification documents and issued a warning ticket to Rodriguez and explained it to him. After doing this, the officer asked for permission to walk his dog around the car. Rodriguez declined. The officer ordered him to stand out of his car while he awaited the arrival of a second officer, and walked his dog around the car. The dog alerted to the presence of drugs that turned out to be methamphetamine, and about seven or eight minutes elapsed between the time the officer issued the warning ticket and the dog’s alert, which increased the total time the car was detained to just under 30 minutes. The lower courts rejected Rodriguez’s motion to suppress in reliance on Eighth Circuit precedents that “de minimis” intrusions on Fourth Amendment rights were tolerable.

Justice Ginsburg distinguished the Court’s holding in Illinois v. Caballes3 on the ground that the dog sniff conducted during a lawful traffic stop in that case was lawful because it occurred while the stop was still underway. She found that everything that the officer did up to the point he asked for permission to walk his dog around the car was legitimately part of a traffic stop, but cautioned that “[a]uthority for the seizure . . . ends when tasks tied to the traffic infraction are—or reasonably should have been—completed.”4 She distinguished the dog sniff from the officer’s various checks because a dog sniff “is not an ordinary incident of a traffic stop.”5 All nine Justices agreed that if the officer had reasonable suspicion that the occupants of the car had illegal drugs (which Justices Thomas and Alito found he did), a brief detention would be justified under Terry v. Ohio6 and its progeny. The majority and Justice Kennedy believed that the Eighth Circuit should be given the first opportunity to decide whether the officer had reasonable suspicion.

Justice Thomas, joined by Justices Kennedy and Alito, argued that a dog sniff was as reasonable a part of a traffic stop as checking for outstanding warrants. Justice Ginsburg could have done a better job of distinguishing warrant checks from dog sniffs by pointing out that typically an officer during a traffic stop will run a check to make sure the registration and driver’s license are valid and the likelihood is that checking for warrants at the same time involves no extension of the time the traffic stop requires and no communication to the occupants of the car that they are being investigated for drugs.

A dog sniff is different, at least for now, for two reasons: (1) most officers making traffic stops do not have a dog in the car; and (2) it would be impractical to bring a dog to the scene of many, if not most, such stops. These realities support Justice Ginsburg’s conclusion that a dog sniff is not ordinarily part of a traffic stop.

Does it make sense to distinguish between the routine incidents of a traffic stop and non-routine, but possible incidents? A couple of hypotheticals can explain why I would say “yes.” Suppose an officer has no dog, stops a car for failing to make a complete stop at a stop sign, checks the driver’s various documents, and issues a ticket. If the officer has no reasonable suspicion of any criminal behavior, it makes no sense to permit the officer to detain someone for almost ten more minutes to await a dog sniff when another officer with a dog can be present. There is nothing “reasonable” about such an arbitrary detention, even though it is for a short time. It might be a short seizure, but a short seizure without reasonable suspicion should be no more tolerable than the small search without probable cause that the Court condemned in Arizona v. Hicks7 and would likely condemn again if the officer in Rodriguez saw a small bag in the back seat of the car and quickly searched it (in 5 seconds) without a warrant or probable cause.

If one is not persuaded, consider an officer who stops a car that has not committed a traffic violation simply because the officer has a dog in the car and would like to do a dog sniff that will take less than two minutes unless drugs are detected, making the stop much shorter than that in Rodriguez. This type of arbitrary, suspicion-less stop was condemned in Delaware v. Prouse.8 Prouse is a reminder that one thing the Fourth Amendment protects against is arbitrary police actions.

Justice Thomas appears to defend “de minimis” delays on the ground that some officers are more efficient than others and that police should not be penalized by being denied the opportunity to do a dog sniff because one officer completes a traffic stop before a dog sniff is possible. In other words, because a dog sniff might occur “during” a stop if an officer was inefficient and there was time for a sniff, as long as the entire stop is not unreasonably long the occupants of a car are no worse off waiting for a dog sniff to occur than waiting for a slow officer to complete a stop that does not include a sniff.

The Court held in Whren v. United States9 that police officers who make traffic stops with probable cause do not violate the Fourth Amendment even if their stops are really “pretexts” for searching for drugs and guns. The Court might want to reconsider whether there are any limits to Whren. Suppose a police department engages in a “slowdown” approach to traffic stops so that many stops take long enough for officers to call for drug-sniffing dogs based on hunches not supported by reasonable suspicion, or that drug-sniffing dogs are placed in every patrol car in a jurisdiction and officers are instructed to use the dogs before completing a stop. The question that would be raised is whether such actions would render these traffic stops “unreasonable” and/or whether the Court is really committed to the proposition that drug-sniffing dogs are not doing searches10 when deployed in these ways. In other words, might a drug-sniffing dog be considered a reasonable component of every routine traffic stop?

1. Rodriguez v. United States, No. 13-9972, slip op. (U.S. Apr. 21, 2015) (majority opinion).

2. Id. at 1.

3. Illinois v. Caballes, 543 U.S. 405 (2005).

4. Rodriguez, slip op. at 5 (majority opinion).

5. Id. at 7.

6. Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968).

7. Arizona v. Hicks, 480 U.S. 321 (1987).

8. Delaware v. Prouse, 440 U.S. 648 (1979).

9. Whren v. United States, 517 U.S. 806 (1996).

10. Place v. United States, 462 U.S. 696 (1983).

Recommended Citation:

Stephen A. Saltzburg, Response, Rodriguez v. United States, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (April 24, 2015), http://www.gwlr.org/rodriguez-v-united-states/.