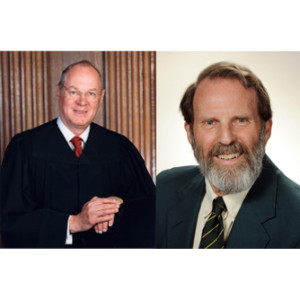

Response by Professor Alan B. Morrison

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (Oct. Term 2014)

Obergefell v. Hodges, 575 U.S. ___ (2015).

Docket No. 14-556; argued April 28, 2015; June 26, 2015

Slip Opinion | New York Times | SCOTUSblog

See End of Post for Reader Comment

With all that was written before and after the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges1 that state law bans on same-sex marriages are unconstitutional, I wondered if I had anything to say that had not been said by others, and probably by quite a few others. But I also thought that, since I had been working with Mary Bonauto of GLAD on these issues starting in the spring of 2009 after she filed the Gill case challenging DOMA, I might have something to say that might be a little different, which explains this essay on three aspects of the decision: (1) Due Process instead of Equal Protection; (2) the failure of the dissents to respond to the Equal Protection claim; and (3) the total lack of justifications in the dissents for the bans, other than the fact that same-sex marriage was a change from the traditional definition of marriage.

Due Process

Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion is almost all about Due Process, with Equal Protection thrown in, almost the way the Justices toss in legislative history to confirm their reading of a federal statute. His prior opinion in United States v. Windsor,2 was also heavily on the Due Process side, but with more Equal Protection and a little federalism included. If there were any doubt that Obergefell is a Due Process opinion, the dissents are all about why Due Process does not carry the day because, in their view, the majority created a new right to a different kind of marriage and the Court’s prior rulings sustaining Due Process only applied where there was a deeply rooted right, which same-sex marriage was not. For Justice Kennedy, the Court’s prior decisions setting aside various limits on who can and cannot be married stand for the proposition that there is a fundamental constitutional right to marry, whereas the dissents saw those cases as holding that there is only a constitutional right for a man to marry a woman, and not for anything more.

Like the Solicitor General,3 I do not believe that Due Process is the proper lens to challenge these same-sex marriage bans. I have always found the argument about the meaning of “marriage” in the prior cases a difficult one to resolve, with the term Due Process providing very little in the way of guidance. In part, that is because making the right a fundamental one also makes it very difficult for a Court to uphold almost any restriction on marriage, including age limits and marriages between relatives. To test the proposition that marriage is a fundamental right, suppose a state decided that it wanted to get out of the marriage business entirely. It would allow religious marriages, keep in place the obligations and rights for previously married couples, and permit future couples to opt into a comparable system of domestic partnerships. People could refer to themselves as married, but the state would no longer confer that label on any couple. If the right is truly fundamental, the state would be acting unconstitutionally under Justice Kennedy’s view, assuming any state would bother to abolish marriage after the Obergefell decision. In addition, the basic polygamy example of one man and two wives is much harder to oppose if there is a fundamental right to marry, as the dissents argue and to which Justice Kennedy’s opinion does not seem fully responsive.

No Equal Protection Defense in the Dissents.

For the challengers to prevail, they only had to win on one ground, but to sustain the law, the states had to turn back both the Due Process and Equal Protection claims. What is perhaps the most surprising aspect about the dissents is that they do not substantively respond to the Equal Protection argument, except to point to the lack of any tradition of having same-sex marriages. Citing the traditional definition of marriage may be a legitimate basis for denying a Due Process claim, but it can hardly suffice for Equal Protection purposes where, no matter what standard of review applies, the state must offer some reason beyond “this is the way we have always done it.” Thus, if tradition were enough, the ban on interracial marriages in Loving v. Virginia4 could have been upheld on that basis.

It is not as though Equal Protection were a minor part of the many cases challenging same-sex marriage bans. The Sixth Circuit in this very case devoted almost all of its discussion on the merits to the Equal Protection claim, upholding the laws here mainly because it saw the preferred treatment for opposite-sex marriages as an appropriate subsidy designed to encourage procreation within marriage. The absence of an Equal Protection defense by the dissenters is surely not a concession by them as to validity of that claim, but it is not unfair to suggest that they felt much more confident attacking Justice Kennedy’s soaring Due Process rhetoric on the importance of marriage and the dignity and respect that it brings to those who are permitted to partake of it, than to providing a legitimate basis for excluding same-sex couples from marriage.

Choosing not to respond to the Equal Protection argument also enabled the dissenters to avoid discussing the everyday, real world harms that same-sex couples suffered from being denied the right to marry. As we demonstrated in Equality Ohio’s amicus brief,5 those state law benefits include income tax advantages, the ability to include a partner in a health plan, the eligibility of state employees to provide pensions for their partners, the ability to adopt a partner’s child, and protection from being excluded from inheriting a partner’s estate. Moreover, all of the federal benefits that the Court in Windsor ruled could not be denied to same-sex married couples could still be denied if the state did not permit such couples to marry.

In the portion of his dissent arguing the inapplicability of Due Process to these bans, Justice Clarence Thomas observed that “the States [have not] prevented petitioners from approximating a number of incidents of marriage through private legal means, such as wills, trusts, and powers of attorney.”6 True enough, but that fails to account for all of the benefits that cannot be achieved by contracts because the state makes them legally unavailable to couples who are not married. The best, albeit unstated, case for the position of the dissenters is that equality may be required so that domestic partners are not excluded from state-conferred benefits, but that does not give them the right to marry.7

Absence of Policy Justifications

Perhaps because the dissenters did not respond to the Equal Protection claim and because under their view of Due Process there was no need to explain why the plaintiffs were not entitled to be married to each other, there are no policy justifications in any of the dissents explaining why same-sex couples should be excluded from marrying beyond the fact they have never been allowed to do so until very recently. There is no claim that (a) the children of same-sex couples will fare less well, (b) men and women are less likely to marry and have children as married couples if same-sex couples can marry, or (c) allowing same-sex marriages will somehow demean opposite-sex marriages—all of which have been advanced at various times in these lawsuits and others. When I say “advanced,” I do not mean that there were live witnesses or anything remotely called evidence that supported those claims, other than the inventiveness of counsel. Moreover, although some of the dissents justify a state’s decision to confer the benefits of marriage on opposite-sex couples, they do not explain why same-sex couples should be excluded from such benefits, especially those relating to the ability of both partners to be the lawful parents of the children of each of them.

While some of the exclusionary justifications appeared in briefs supporting the states in Obergefell, not one of them appears in any of the dissents. The likely response of the dissenters would be that the Constitution does not require judges to have evidence when there is only rational basis review. But even then the Court has insisted that there be some reason, even if not articulated by the legislature or supported by witnesses at trial. It is the absence of even that minimal rational basis in any of the dissents that is most telling and explains why the time was ripe for this ruling and why the country will accept the decision and move on. If no dissenting Justice can state a policy justification for why same-sex couples should not be allowed to marry and to obtain all the rights and obligations of comparable opposite-sex couples, then surely the principle of equality enshrined in our Constitution must be read to end the bans on same-sex marriages, which is just what the Court did.

Reader Comment

“I served as cooperating counsel with GLAD on Connecticut’s marriage case, Kerrigan v. Commissioner of Public Health, 289 Conn. 135 (2008). Last week I wrote a blog post for our firm’s website comparing Kerrigan and Obergefell in which I noted that the SCOTUS dissenters largely avoided addressing the issues raised, in contrast with the Kerrigan dissenters who addressed all the claims at length. It is particularly striking that the Obergefell dissenters ignored the equal protection claims in light of their dissents in Windsor. Three of the Windsor dissenters thought the Court lacked jurisdiction, which should have been the end of the analysis, yet they went on to opine on the merits. Perhaps the dissenters in Obergefell realized that any substantive analysis would necessarily entail an attack on gay people and that it was better to attack the process.”

–Kenneth J. Bartschi | Horton, Shields & Knox, P.C. | July 6, 2015; 10:23 AM

Dean Morrison filed a brief amicus curiae on behalf of Equality Ohio in support of the petitioners.

1. No. 14-556, slip op. (U.S. June 26, 2015).

2. 133 S. Ct. 2675 (2013).

3. Obergefell, slip op. at 9 (Roberts, C.J., dissenting)

4. 388 U.S. 1 (1967).

5. Brief for Equality Ohio et al. as Amici Curae at 6-12, Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___ (2015) (No. 14-556), http://sblog.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/14-556-14-562-14-571-14-574-tsac-Equality-Ohio.pdf.

6. Obergefell, slip op. at 10 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

7. Id. at 24 (Roberts, J., dissenting) (suggesting the possibility that a case challenging denial of benefits for same-sex couple might be stronger than a claim to the right to marry).

Recommended Citation

Alan B. Morrison, Response, Obergefell v. Hodges, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (June 19, 2015),http://www.gwlr.org/obergefell-v-hodges/.