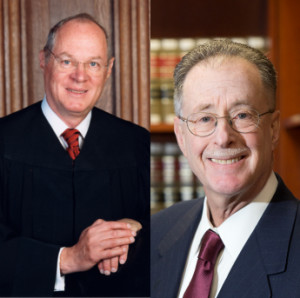

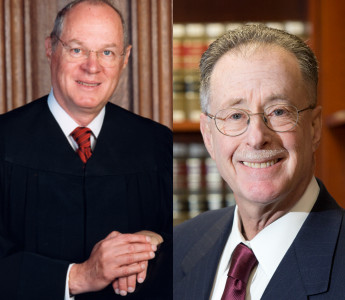

Molina-Martinez v. United States, 578 U.S. ___ (2016) (Kennedy, J.).

Response by Professor Stephen A. Saltzburg

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (Oct. Term 2015)

Slip Opinion | New York Times | SCOTUSblog

When Guidelines Affect Substantive Rights

Saul Molina-Martinez pleaded guilty to being unlawfully present in the United States after having been deported following an aggravated felony conviction. The Probation Office prepared a pre-sentence report which described the offense of conviction, the defendant’s criminal history and personal characteristics, and the available sentencing options.

The Report contained the calculation by the Probation Office of the correct guideline to be applied given the offense and the defendant’s criminal history. The Report calculated the correct guideline range to be seventy-seven to ninety-six months. At the sentencing hearing Molina-Martinez’s counsel argued for a sentence of seventy-seven months, the low end of the guideline range, while the government argued for a sentence of ninety-six months, the high end of the guideline range. The district court stated it was adopting the Report’s factual findings and guideline calculation and imposed a sentence of seventy-seven months imprisonment followed by supervised release for three years “without supervision” (something of an oxymoron).1

On appeal, Molina-Martinez’s counsel filed a brief pursuant to Anders v. California,2 stating that there were no nonfrivolous grounds for appeal. But, Molina-Martinez filed his own brief and identified what he believed was an erroneous guideline calculation. The court of appeals directed his lawyer to file either a second Anders brief or a brief on the merits of the guideline issue. The lawyer’s new brief argued that the Probation Office had misapplied a guideline provision on how to compute criminal history when more than one sentence was imposed on the same day. Molina-Martinez had been sentenced on five burglary charges on the same day, and the new brief argued that, had the criminal history been properly calculated, the correct guideline range was seventy to eighty-seven months. The court of appeals appeared to agree with the argument that the guideline range used by the district court was erroneous.

Because Molina-Martinez had not objected to the guideline calculation in the district court, his only recourse on appeal was to argue that the court of appeals should declare the sentencing mistake to be plain error pursuant to Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 52(b): “A plain error that affects substantial rights may be considered even though it was not brought to the court’s attention.”3 The Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Olano4 established that a showing of plain error requires (a) that an error not have been intentionally relinquished or abandoned; (b) the error must be clear or obvious; and (c) the error must have affected substantial rights, which means that the defendant must show a reasonable probability that the outcome would have been different but for the error.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit declined to find plain error because it concluded that Molina-Martinez could not show that his substantial rights were affected, due to the fact that the sentence of seventy-seven months that actually was imposed fell within the correct guideline range of seventy to eighty-seven months and there was no showing of additional evidence in the record to demonstrate that the guidelines had an effect on the district court’s selection of the sentence that was imposed. The U.S. Supreme Court granted review because the Fifth Circuit’s approach to plain error was inconsistent with that of other circuits.

Justice Kennedy delivered the opinion of the Court and was joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan. Justice Kennedy summarized the approach of other circuits: “other Courts of Appeals have concluded that a district court’s application of an incorrect guideline range can itself serve as evidence of an effect on substantial rights.”5

In Part I of his opinion, Justice Kennedy described the way in which the federal sentencing guidelines operate to achieve uniformity and proportionality, observed that the guidelines are complex and that errors in guideline calculation might go unnoticed, and noted the availability of plain error review. In Part II of his opinion, he described the positions taken in the district court by the parties and the Fifth Circuit’s analysis.

Then, in Part III, Justice Kennedy emphasized that “[t]he Guidelines’ central role in sentencing means that an error related to the Guidelines can be particularly serious,”6 because “the Guidelines are not only the starting point for most federal sentencing proceedings but also the lodestar.”7 Because “[t]he Guidelines inform and instruct the district court’s determination of an appropriate sentence,” Justice Kennedy reasoned that “[i]n the usual case, then, the systemic function of the selected Guidelines will affect the sentence.”8

Contrary to the Fifth Circuit’s analysis, Justice Kennedy concluded that the central role that the guidelines play in federal sentencing means that a defendant who can show that a sentencing court used an incorrect guideline range “should not be barred from relief on appeal simply because there is no other evidence that the sentencing outcome would have been different had the correct range been used.”9

Justice Kennedy rejected the government’s argument that permitting a defendant to show prejudice (i.e., that substantial rights were affected) through the fact of a guideline error alone meant that there was no real difference between Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 52(a) (Harmless Error) and Rule 52(b) (Plain Error). He concluded that, although both Rules require an analysis of whether an error was prejudicial, the government has the burden of demonstrating harmless error under (a) whereas the defendant can rely on a guideline error to show an effect on his substantial rights under (b). And he also rejected the government’s argument that re-sentencing would be a drain on judicial resources, observing that re-sentencing occurs in a small fraction of cases and is less burdensome than retrying an entire case.

Justice Alito, joined by Justice Thomas, concurred in part and in the judgment. He agreed with Justice Kennedy that the Fifth Circuit’s analysis was incorrect and that Molina-Martinez did show a reasonable probability that the district court would have imposed a different sentence had it used the correct guideline calculation. Justice Alito was unwilling to speculate, however, about how often the reasonable probability test would be satisfied in future cases, especially given the fact that the impact of the guidelines might be affected by the replacement of judges who spent decades applying mandatory guidelines with judges who are using advisory guidelines to which they might be less wedded.

1. Molina-Martinez v. United States, No. 14-8913, slip op. at 6 (U.S. Apr. 20, 2016) (majority opinion).

2. Anders v. California, 386 U.S. 738 (1967).

3. Fed. R. Crim P. 52(b)

4. United States v. Olano, 507 U.S. 725 (1993)

5. Molina-Martinez, slip op. at 2 (majority opinion).

6. Id. at 9.

7. Id. at 10.

8. Id.

9. Id. at 11.

Recommended Citation:

Stephen A. Saltzburg, Response, Molina-Martinez v. United States, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Docket (Apr. 27, 2016), http://www.gwlr.org/molina-martinez-v-united-states-when-guidelines-affect-substantive-rights/.